Why the US and China are watching Panama closely

A Closer Look at the Panama Port Deal

The Panama Canal is one of the world's busiest shipping lanes. And right now, it could be on the brink of a strategic shift.

Two ports at both gateways of the canal — Balboa and Cristóbal — might just change hands in a $22.8 billion deal. These ports handle nearly 39% of the canal's container traffic — about 3.74 million TEUs annually — and oversee more than 12,000 ships that pass through the canal each year. If approved, the world's largest shipping company, MSC, and BlackRock's infrastructure fund will take them over from Hong Kong's CK Hutchison.

Their sale, though, isn't a mere commercial agreement. It's a matter of global power dynamics.

These companies stand to buy a piece of one of the world's most important geopolitical chokepoints. And that's why this deal has landed up at the center of a major international diplomatic tussle.

Why Panama is central to the world's supply chains

The Panama Canal is one of the world's most important trade shortcuts.

The canal cuts through the heart of Central America. In doing so, it creates a shortcut between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans: where any ship can quickly pass between the Eastern and Western sides of the Americas. Without it, ships would have to travel another 8,000 nautical miles for the voyage — all the way around South America's Cape Horn.

If you ever need to by-pass the Americas — if you're transporting something from Japan to New York, or from Europe to San Francisco, or even within the United States, between its two coasts — the 8,000 nautical miles you save can shave off weeks in transit times, and millions of dollars in fuel.

This is why the canal is always in such heavy use. Today, around 5% of global maritime trade — roughly 423 million tons of goods every year — passes through this single, narrow corridor.

The importance of the canal is all the more obvious when the Suez canal — a similar shortcut by-passing Africa — is out of action. Earlier this year, for instance, tensions in the Red Sea disrupted traffic through the Suez Canal. Cargo from Asia to the American East Coast was re-routed through the Pacific ocean, via the Panama Canal. Suddenly, the canal saw a large spike in rerouted traffic. The canal was, in essence, a pressure valve for global shipping.

But there's a flip side to this. If the Panama canal ever stops flowing, global trade takes a severe beating. Trade to and from the Americas, in particular, can suddenly stall. In 2023, for instance, a severe drought made it difficult to operate the canal, forcing authorities to limit daily ship transits. Overnight, this created long queues outside the canal, driving up freight rates.

The canal is, in short, a chokepoint. And as we've often mentioned on The Daily Brief, in the cut-throat world of international trade, any chokepoint is simultaneously a point of leverage.

The two mouths of the canal

Panama has drawn geopolitical interest for more than a century.

The canal was never a local, Panamanian project. From the very beginning, it was conceptualised, and then constructed, by hegemonic powers — it began as a French project, which was taken over by the United States. The United States always saw it as a passage for its naval and commercial ships. For over 80 years from the point the canal was first constructed, it was entirely under US control. America also built a large number of military bases flanking the canal, to remind the world of who held sway over this vital maritime artery.

That grip began to loosen in the 1970s. Panama had always been sore about how America controlled something so strategically important, which ran right through its territory. Those tensions hit a boiling point over the 1960s and 1970s. The two sides eventually signed the Torrijos-Carter Treaties of 1977, which promised full Panamanian control over the canal by 1999. This came with an obligation, however: Panama was to keep the canal open to ships from any country at all times — even in a case of war.

That shift wasn't smooth. In 1989, for instance, the U.S. invaded Panama — supposedly in "self-defence". One of its key goals was to ensure its control over the canal.

For around 25 years now, however, the canal has stayed in Panamanian hands. But that peaceful interregnum might be ending. Global powers once again vie for influence over the canal. China, in particular, has been courting Panama under its belt-and-road initiative. And that has raised concerns in the United States.

A lot of this international interest, currently, targets its two access points.

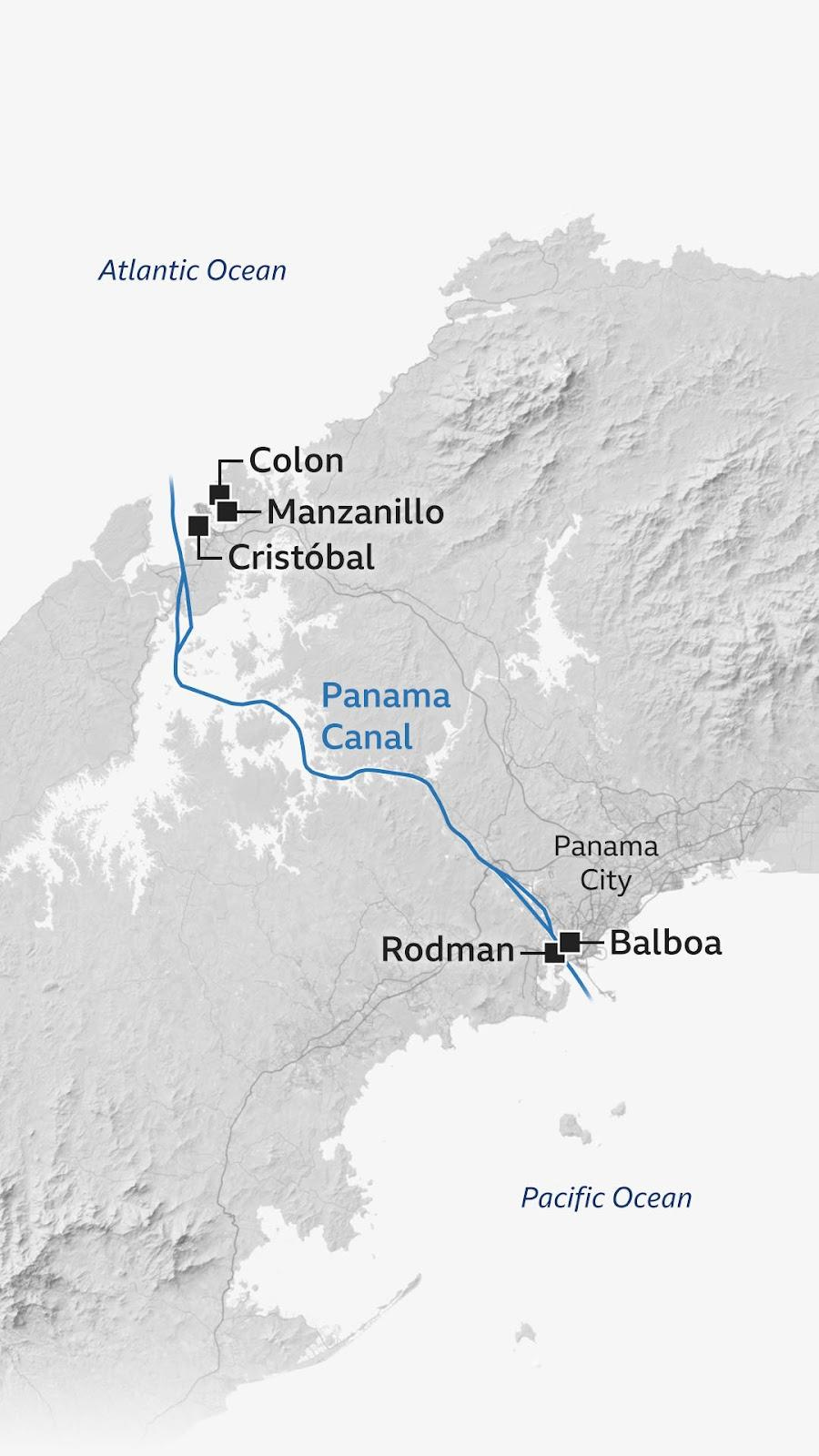

At the Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal is the Port of Balboa. At the other end, guarding the Atlantic mouth of the canal, is the port of Cristóbal. Together, both are critical access points to the canal.

To be fair, these don't have a monopoly. Panama has other terminals, like PSA Rodman or Manzanillo. But none of them match the geographic and operational importance of Balboa and Cristóbal. Between them, the two ports control nearly half of the country's container traffic. They're effectively the entry and exit points of the Panama Canal.

A large part of their business, in fact, revolves around "transshipment" — that is, ships unload their cargo at these ports, where it is then redistributed to other vessels. These ports are frequented by large ships from all over the world, that pick goods up from, and deposit goods to, these points. Then, that cargo moves to a network of small feeder ships that serve ports all across the Americas. This puts them at the very heart of American maritime trade.

The deal

It is these critical ports that might now change hands. At stake is control over one of the world's busiest trade routes.

MSC's Terminal Investment Ltd. (TiL), the port-operating arm of shipping giant MSC, has teamed up with BlackRock's Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP) to acquire control of the two ports, for the headline-grabbing price tag of $22.8 billion. At the other end is Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison.

The deal, in fact, goes deeper than these two key ports alone. If the deal goes through. TiL and GIP will also gain minority stakes in 41 other port-related assets around Panama, including valuable land parcels, rail connections, and associated infrastructure — essentially giving them influence over the broader logistics and transport ecosystem surrounding the canal. Hutchison retains only a minor residual stake.

But there's the problem. CK Hutchison is a company based in Hong Kong. While it doesn't have a direct connection to the Chinese state, it still operates under the shadow of the Chinese Communist Party. Both MSC and Blackrock, on the other hand, are decidedly oriented towards the West.

And so, to China, this looks like strategic encroachment by Western interests. Chinese state media and strategic commentators have framed the deal as a loss of critical infrastructure. And China is doing whatever it can to grind the deal down.

Right now, the mega-transaction hinges on approval from Panama's Maritime Authority and the Panama Canal Authority (ACP), which are caught in a cross-fire between the United States and China. Chinese authorities, meanwhile, have been putting considerable pressure on CK Hutchison to cancel the sale. It might try using anything from antitrust laws to its national security laws to try and scuttle the deal.

The parties have set a deadline of July 27 for the deal to be finalised. Beijing is actively trying to collapse the deal before that date, or is at least threatening to do so in order to extract tariff concessions from the United States.

Why is Beijing so worried

Not very long ago, Beijing would have thought it had a strong hand in Panama.

For many years, Panama didn't recognise China as a legitimate country — preferring to maintain formal relations with Taiwan instead. But things began to thaw in 2017. Panama withdrew its relations from Taiwan, embracing China. The two countries began trade talks, and a year later, in 2018, Panama became the first country to join China's Belt-and-Road Initiative. It quickly became a symbolic cornerstone in the initiative's expansion into the Western Hemisphere.

It was during this time that Panama extended CK Hutchison's contracts over the Balboa and Cristóbal ports for 25 years, beginning in 2021.

But when Donald Trump became the American President, he immediately pushed the country to abandon its ties with the Chinese. The two super-powers began a tug-of-war for the country's loyalty. Under pressure, Panama formally exited the Belt and Road Initiative — much to China's dismay.

To the United States, the deal is a diplomatic and strategic win. It diminishes China's operational influence in its geopolitical backyard. China, meanwhile, is deeply unhappy.

What is it afraid of? Primarily, it's this: while the Panama canal is neutral in theory, anyone that controls the ports at Balboa and Cristóbal can influence all the trade that flows through.

This influence can be subtle. Port operators influence key decisions: from berth scheduling, to terminal fees, to cargo processing times. They can play favourites here, prioritising certain shipping lines or countries, while squeezing competitors by slowing them down. If a future port owner slaps high terminal charges on a country, or only gives it inconvenient berthing schedules — it can penalise that country while technically staying within the bounds of neutrality.

In a more extreme scenario, however, these could become points of hard power projection. If there's ever a geopolitical flashpoint — operators could deny vessel access outright under various pretexts, effectively cutting countries off the trade route. We've seen this before: the chokepoints at Djibouti and the Suez Canal have previously been used for political leverage.

Ports could also become intelligence-gathering hubs. Infrastructure and tech installed for port operations could quietly collect data, monitor rival supply chains, or even, in theory, enable cyber disruptions.

This is why, at the very least, China wants a seat at the table. Even if it can't stop the sale from going through, it wants some point of leverage. For instance, recent leaks suggest China's state-owned shipping giant COSCO is in advanced talks to buy a minority stake in the MSC-led consortium. If successful, China could reinsert itself into the ports' governance, preserving at least partial access to the two chokepoints.

The bottomline

Under the guise of a commercial deal, what we're seeing, perhaps, is a strategic realignment.

Control over Balboa and Cristóbal means influence over how the Panama canal operates in practice, even if not in name. That's why it has received so much attention from Beijing and Washington. The United States sees this as an opportunity to reassert control in its hemisphere. China, on the other hand, faces a loss of leverage in a critical corridor.

Stuck between the two is Panama, for whom this has become a brutal test: of whether it can stay neutral when the ports at both ends of its canal become pawns in a global power contest.

Comments

Post a Comment