Yesterday, we had looked at India's ports industry, and its crucial role as "the lungs of our economy". The vast majority of the goods we bought and sold as a country — 90% by volume, in fact — touched our ports at some point.

But knowing that ports matter is one thing. Understanding the actual businesses that run them is quite another. So, like we promised last time, we'll dive into two companies that sit behind the scenes as cargo moves in and out of India: Adani Ports, and JSW Infrastructure.

These entities are at an interesting juncture. As we'll soon see, some of our biggest port players aren't just running ports anymore. They're building something much more ambitious.

Adani Ports

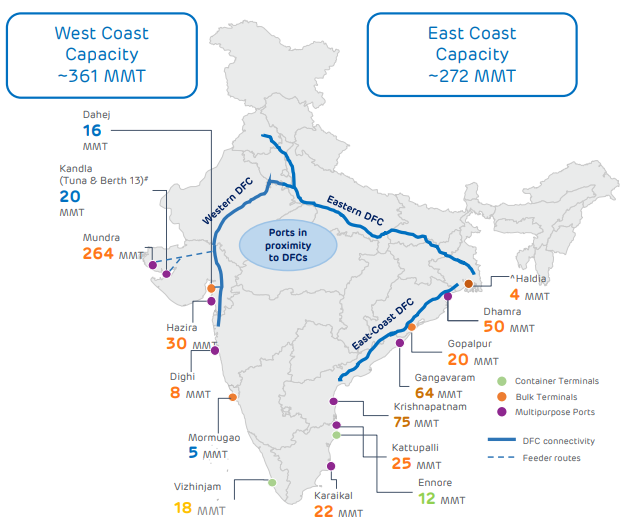

Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Ltd (APSEZ) is India's largest private port operator. It runs 15 ports and terminals across the Indian coastline, capturing 27% share of all cargo handled in the country.

Its flagship port, at Mundra in Gujarat, is now the first port in India to cross 200 million metric tonnes (MMT) in a year.

That is impressive in itself. But it only scratches the surface. See, Adani Ports is in the process of re-writing its entire business.

Adani is coming for the entire supply chain

For decades, port operators made money in a fairly straightforward way. When a ship arrived, they charged for letting it dock. When cargo needed unloading, they charged for that too. And maybe they would store some containers for a few days and collect storage fees.

This was a volume game. The more ships that came, the more money you made. Your fortunes rose and fell with global trade cycles.

But about a decade ago, APSEZ started thinking about this differently. They began asking: why only touch cargo when it's at the port? Why not control its entire journey?

Think about what happens when a container arrives from, say, China.

First, it gets unloaded at the port.

Then, a truck picks it up and takes it to a railway yard.

Then, a train carries it to an inland depot.

From there, another truck takes it to a warehouse.

And eventually, yet another vehicle delivers it to its final destination — maybe a factory in Haryana or a distribution centre in Pune.

Here's what it looks like:

At each step, different companies handle the cargo, and each takes their cut. But what if one company could do it all?

This is what APSEZ is trying. They started expanding beyond the waterfront, to buy their own trains: 132 rail rakes to be precise. They also built inland logistics parks in cities far from the coast, setting up 3.1 million square feet of warehousing. At the other end, they acquired a fleet of 115 vessels for marine services. And they even created tech platforms to manage trucking and freight forwarding.

A company that once just ran ports, in short, is slowly turning into what they now call an "integrated transport utility." In the words of Mr. Divij Taneja, the CEO of Adani Logistics:

"You're seeing us move from custodians to exhibiting control over cargo."

The financial logic behind this transformation is fairly intuitive. Let's say unloading a container earns you ₹100. That's what a traditional port operator would make. But if you also move that container on your own train, store it in your warehouse, and deliver it using your trucking network, you could earn, say, ₹500 from the same container. More touchpoints mean more revenue, and crucially, higher margins as well.

Adani's business in numbers

You can see this shift in their numbers. In FY 2025, Adani Ports handled 450 million metric tonnes of cargo, which is about 7% more than the previous year. But their revenue jumped 23%, while their profit surged 50%. How does a 7% growth in volumes translate to a 50% profit growth?

That is the story of Adani's changing business model.

Three things are driving this transformation.

First, the type of cargo is shifting. We spoke about this yesterday: as our economy grows more sophisticated, containers, which carry higher-value goods like electronics, textiles, or auto parts, are growing faster than bulk cargo like coal or iron ore. That's what Adani is seeing. Containers now make up 45.5% of Adani's total cargo, up from 44% a year ago. And because container cargo involves more steps in the supply chain, it offers more opportunities to earn revenue.

Second, its 'non-port businesses' are taking off. That's the shift we were referring to. Their logistics arm grew revenue by a massive 39%, to ~₹2,881 crore last year. Marine services, which include things like dredging harbors, supporting offshore operations, and guiding ships, grew even faster, jumping by an incredible 82% to ~₹1,144 crore. What used to be side businesses, in essence, is now becoming a major revenue driver.

Third, they're getting better at squeezing profits from existing operations. Even with modest volume growth, they've expanded margins through smarter pricing, while controlling costs. Equally, the company is focusing on making sharper investments that generate quicker returns. Their domestic ports, in fact, are returning all the capital they've invested in less than five years — in an industry where returns would previously come in as long as a decade.

Impressively, these improvements in their business have coincided with them slashing down their debt. Their net debt relative to earnings has fallen from 2.3 times to 1.9 times over the last year. They repaid ₹5,500 crore of debt last year and ended with nearly ₹9,000 crore in cash.

Their future investments — slated to be around ₹11,000-12,000 crore next year — will come entirely from their own profits, and not any new borrowing.

Internationalisation

Adani's ambitions aren't just limited to India. They've also been building an international network.

For one, they run Haifa Port in Israel. Many initially thought this was a risky bet, given the region's tensions. But they've managed to stabilize those operations. They've signed long-term union agreements, and are now seeing double-digit profit growth.

That's just one of their foreign forays. They've also started operations at a terminal in Colombo, Sri Lanka, have won a 30-year concession to run Dar es Salaam port in Tanzania, and are acquiring a major coal terminal in Australia that could handle 50 million tonnes annually.

This international expansion is like an insurance policy for the business — allowing it to diversify its bets in a heavily capital-intensive sector. If India's trade slows down due to a recession or policy changes, having ports in other high-growth regions provides stability.

JSW Infrastructure

JSW Infrastructure is India's second-largest private port operator. At the end of FY 2025, the company had 177 million tonnes per annum of operational port capacity – across 10 ports and terminals strategically located on both the east and west coasts of India. These ports aren't just piers and cranes; many are deep-draft facilities capable of handling large ships.

Right now, JSW Infrastructure is taking an approach which is very different from Adani's, but equally interesting: it plans on becoming a full-stack logistics enabler for heavy industries.

JSW's heavy industry play

While Adani is building a global, multi-modal network that can handle any type of cargo, JSW Infra is sharpening its scope instead, focusing on becoming the go-to logistics partner for India's heavy industries.

That is why, unlike Adani Ports, which is slowly moving towards containerised cargo, the strength of JSW Infra's ports lies in bulk cargo — things like coal, iron ore, and liquid cargo. (If this sounds alien to you, check out yesterday's edition.)

What distinguishes their business, though, is their integration. Many of JSW's ports are connected directly to steel plants, power stations, and mines through dedicated rail lines and also slurry pipelines.

Imagine this: you're in the business of exporting iron ore, but you don't have to load it all onto trucks which drive all the way to the coast, killing your already razor-thin margins. What if, instead, you can grind it into a fine powder, mix it with water, and pump it through a 302-kilometer pipeline to the port directly? That's exactly what JSW is building in Odisha. While this might sound almost absurd, this is actually one of the most efficient ways to move bulk materials over long distances.

This tight integration creates customer stickiness for them, because customers' operations are now built around the infrastructure that JSW provides. For instance, imagine you're running a steel plant. If your coal arrives at a specific port, and your iron ore comes through a particular pipeline, then your entire operation is designed around your logistics provider's network. Switching to someone else would mean rebuilding everything from scratch, which you would want to avoid doing unless absolutely necessary.

JSW has built this network out in the recent past. They started out serving only their parent company's steel and power plants. But today, half their cargo comes from outside customers who've built their operations around JSW's infrastructure.

The numbers

The company's fourth-quarter results show how this model is working.

Over Q4 last year, its revenue grew 5% to ~₹1,152 crore. But the company's net profit for Q4, on the other hand, jumped 57% to ₹516 crore.

Now, don't let that figure fool you. The operating profits of the company were nowhere as impressive. The company's EBITDA for the quarter grew by a far more modest 8% — to ₹626 crore. Some of the profit jump came from one-time currency gains, while the company essentially had to tax outgo over the quarter.

Expansion plans

Regardless, the underlying business is clearly strengthening. The company is bringing more capacity online: with ~1 million tonnes of new capacity coming up over the quarter. This is slated to grow over the coming quarters.

The company is ramping up the capacity of its existing ports. At South West Port in Goa, for instance, the company expanded from 8.5 to 11 million tonnes per annum. It's in the process of getting regulatory approvals for a further expansion — all the way to 15 MTPA.

Meanwhile, JSW Infra is expanding beyond ports as well. They recently bought 70% of Navkar Corporation, which runs inland container depots and freight stations. Here, containers can be sorted, stored, and distributed, en route to whatever destination it must finally get to. It's basically one more way to capture more value from each shipment.

The bottomline

What we're witnessing right now with both these companies is a fundamental shift in how the logistics business works in India. The old model was simple — you owned a piece of key infrastructure, and you used it to charge tolls. But these players are now thinking about owning the entire journey.

This transformation matters for several reasons. Their customers need to deal with fewer vendors, while getting more predictable service. For these companies, meanwhile, it means higher margins and more stable revenues. For India's economy, it means more efficient trade infrastructure that can handle growing volumes without proportional increases in cost.

Both Adani Ports and JSW Infrastructure are betting that India's trade ambitions will keep growing. And they're positioning themselves to capture not just a slice of that growth, but the entire pie, right from the moment a ship appears on the horizon to the moment its cargo reaches its final destination.

Tidbits

Dassault Expands India Partnership, to Manufacture Falcon 6X and 8X Jets with Reliance

Source: Business Standard

Dassault Aviation has announced a significant expansion of its joint venture with Reliance Aerostructure Ltd at the Paris Air Show, marking a first in Falcon jet manufacturing outside France. The Dassault Reliance Aerospace Ltd (DRAL) facility in Mihan, Nagpur—already responsible for delivering over 100 major subsections of the Falcon 2000 since 2019—will now be upgraded to a Centre of Excellence. This facility will handle manufacturing and assembly for the Falcon 2000, as well as the upcoming Falcon 6X and flagship 8X models. DRAL is a 51:49 joint venture between Dassault and Reliance, originally set up in 2017. Dassault's decision positions India as a core part of its global supply chain and marks a notable milestone in the country's ambitions to scale high-value aerospace manufacturing under the Make in India initiative.

Welcure Secures ₹517 Cr Sourcing Deal with Thai Firm, Eyes ₹26 Cr in FY26 Service Income

Source: Business Line

Welcure Drugs & Pharmaceuticals Ltd. has signed a ₹517 crore third-party sourcing agreement with Thailand-based Fortune Sagar Impex Company. Under the ex-works model, Welcure will earn a fixed 5% commission on the transaction value, translating to an expected service income of ₹26 crore in FY26. The deal involves procurement of multiple finished-dosage SKUs, with all downstream responsibilities—including packaging, freight, and regulatory clearances—handled by the Thai partner. The structure allows Welcure to avoid inventory risk and manufacturing commitments, supporting an asset-light model with high-margin potential. The company aims to leverage this agreement to scale its fee-based services without straining its balance sheet.

India's $89 Billion Clean Industrial Pipeline Sees Slow Progress, Only One Project Reaches Final Investment Decision

Source: Reuters

India's clean industrial transition faces a critical slowdown as only one out of 41 announced projects, worth a cumulative $89 billion, has reached Final Investment Decision (FID) in the past six months. Despite a strong pipeline in sectors like green ammonia, hydrogen, and sustainable aviation fuel, just $13 billion has been committed so far. In comparison to global figures, 83% of the 826 clean industrial projects worldwide are still awaiting financing, highlighting a broader investment challenge. Key obstacles include high capital costs, underdeveloped commodity markets, and policy uncertainty. The report flags that India's progress is significantly behind countries like China and the U.S. in terms of actual capital deployment. Without timely financial closure and execution, India's goal to decarbonize hard-to-abate sectors risks being delayed.

Comments

Post a Comment